Reports and articles

Forging ahead: ten years of growth and innovation for the UK food and drinks sector

Published on January 11th 2024

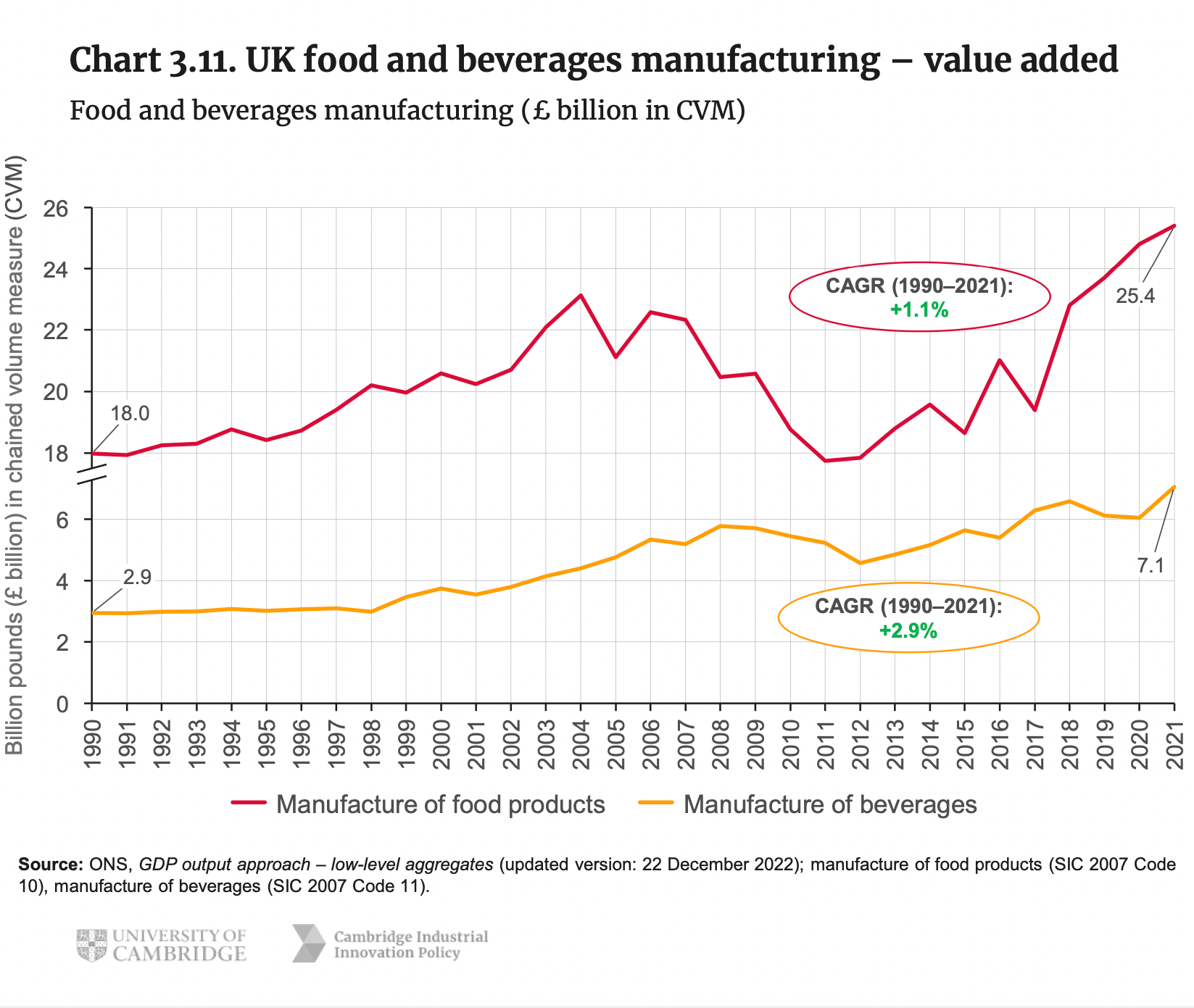

In the last decade, the UK’s food and beverage sector has experienced remarkable growth, achieving notable progress in value-added offerings, global rankings, and research and development (R&D) expenditures. The UK ranked sixth among OECD member countries for food and beverages manufacturing in 2019 by value-added, highlighting the sector’s substantial role in the country’s economic landscape.

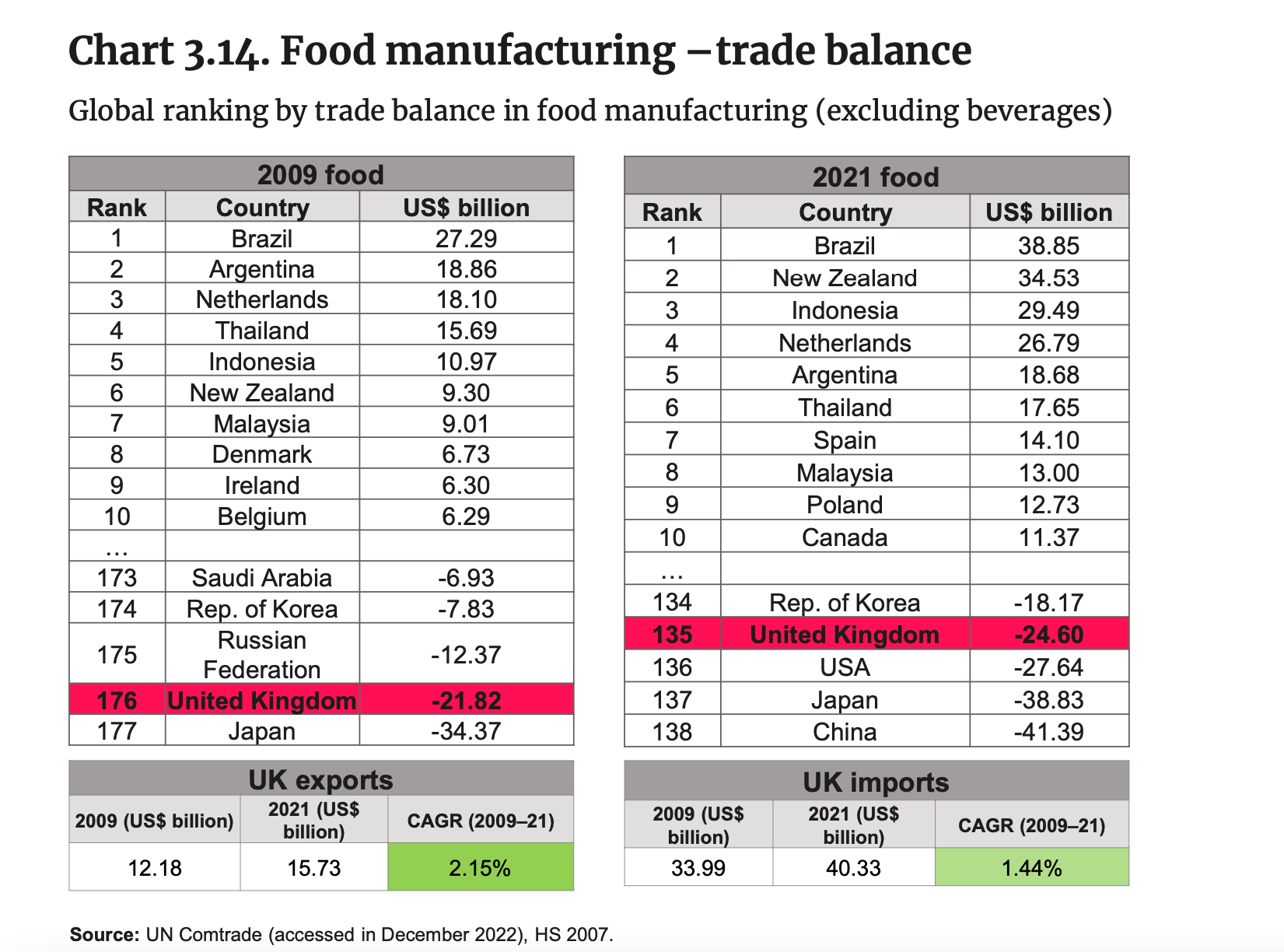

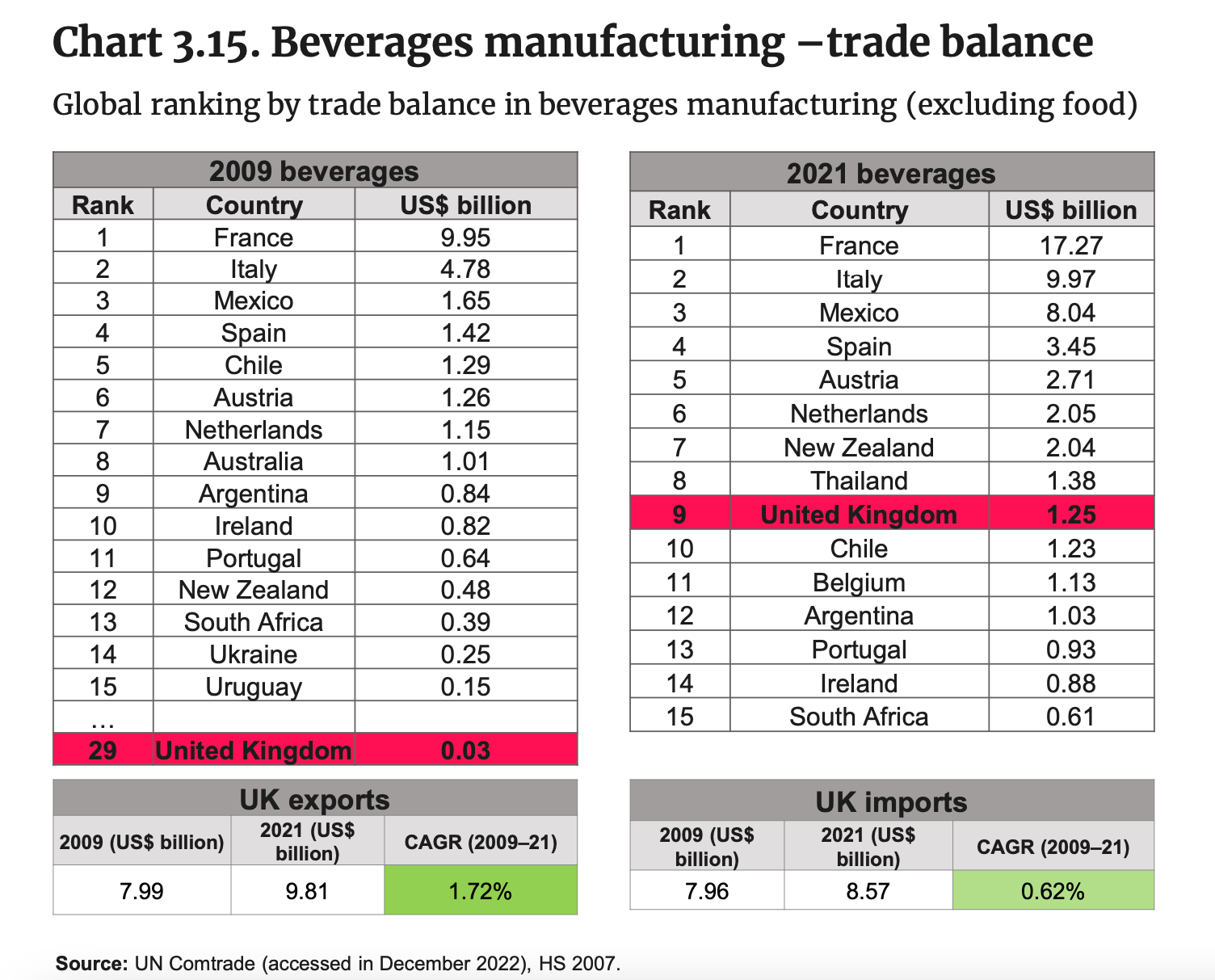

However, despite this, the UK faces challenges in its food trade balance, with one of the largest food trade deficits among comparator countries. The UK occupied the lower position in the global food trade balance ranking in 2021, with a deficit of US$24.6 billion. In stark contrast, it excelled as a leading exporter of beverages, securing the ninth position globally in the beverages trade balance ranking for 2021 with a surplus of US$1.25 billion.

For the 2023 Innovation Report published annually by Cambridge Industrial Innovation Policy, we consulted sectoral experts and reviewed the literature to understand why the UK food and beverage sector’s value added has increased in the last decade, which is why the UK has one of the most significant food trade deficits among comparator countries despite being a leading exporter of beverages.

Five key themes that arose from these discussions:

- Sector resilience

- The consulted stakeholders largely agreed that because food and beverages are essential customer goods, domestic demand for UK food and beverages tends to be more stable than products from other sectors.

- Competition among grocery retailers reduces prices and shapes consumer preferences based on value propositions. [MakeUK, 2020].

- Sector resilience was demonstrated during the 2008 financial crisis. Between May 2008 and May 2009, the production index for food and drink fell by 1.9, compared to 13.1 for manufacturing overall. Exports grew 5.4% in the first nine months of 2009, compared with the same period in 2008, compared with the -14.3% performance for all UK commodity exports during the same period [IfM, 2010].

- UK household and eating-out expenditure on food and drink increased between 2001 and 2020 (including during the 2008 financial crisis). Although expenditure was reduced in 2021 because of COVID-19, this is attributed to a fall in food and beverages eaten out of the household as a result of restaurants and other licensed premises being shut for large parts of the 2020–21 pandemic period [DEFRA, 2022; DEFRA, 2023].

- Stakeholders highlighted that UK food and beverage sector resilience is supported by adaptable and flexible supply chains, which have traditionally been capable of resisting external shocks (e.g., economic, climate, trade, transportation, labour) [DEFRA, 2021].

- Close collaboration between the government and the private sector to monitor, anticipate, and respond to risks adds to the resilience of UK food and beverage supply chains [DEFRA, 2021].

- Prioritisation of domestic markets

- The UK produces around 60% of its domestic food consumption by economic value, part of which is exported, including the majority of grains, meat, dairy and eggs, rising to 75% for food that can be grown in the country [DEFRA, 2022b]. This solid and consistent domestic production, combined with a diversity of international supply sources that avoids over-reliance on any one source, translates into a resilient UK food supply, albeit one that needs to be entirely self-sufficient.

- The interviewees suggested that food and drink manufacturers’ exports are a secondary priority given the large and consistent domestic market. Potential export barriers identified by stakeholders included product shelf life and the fragile nature of their products [FDF, 2017].

- The necessity of Imports

- The consulted stakeholders shared that the UK cannot produce all of the foods because of geography, weather resources and land availability and suitability. This means that some ingredients and products will inevitably have to be imported.

- The production-to-supply ratio has remained stable over the last two decades, and for crops that can be commercially grown in the UK, this has been around 75% [DEFRA, 2021].

- Products that cannot be produced in the UK, such as rice, must be imported. These are essential products for consumer consumption and constitute key inputs for UK manufacturing industries such as the milling industry [DEFRA, 2002b].

- Furthermore, imported products and raw materials not produced in the UK, such as tropical ingredients, help to extend the availability of produce outside their growing season in the UK [FDF, 2022].

- Ready-meal market growth

- The consulted stakeholders highlighted that the last decade saw a move by food retailers towards introducing ready meals at a scale that most likely supported the overall growth of the food and drinks manufacturing sector in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis.

- The UK ready meal market experienced significant growth between 2008 and 2022, with sales of ready meals totalling £3,733 million in 2022, compared to £2,450 million in 2008 [Euromonitor Database, 2023]. The top three retailers by share of ready-meal sales in 2022 included Tesco (17.8%), Marks & Spencer (12.2%) and Sainsbury’s (10.7%) [Euromonitor Database, 2023].

- Driving profits: Alcoholic drinks at the helm

- Alcoholic beverages represented the third-largest share of businesses, with roughly the second-highest turnover and highest profits before taxes, above meat and meat product businesses, which had the fifth-highest profits before tax [FDF, 2017].

- The sub-sector not only had the largest share of businesses in the sector over the 2013–15 period but also generated the highest turnover and second-highest profits before taxes, only after the profitability of alcoholic beverage manufacturers [FDF, 2017].

Adapting for growth: Challenges shaping the future of UK food & beverages

Several concerns will shape policy and industrial strategy to foster future growth in the UK’s food and beverage sector.

Rising energy costs – One pressing challenge is the impact of inflation and rising energy costs intricately linked to the manufacturing of food and beverages. As indicated in consultations, stakeholders emphasise the direct connection between energy and input costs and the overall cost of production. The surge in energy and input prices witnessed in 2021–22 has been transferred to consumers, affecting food prices. The ongoing energy crisis, which took root in 2022, poses a particularly formidable challenge for major energy users within the sector, such as bakers and millers. Statistics from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) underscore the widespread effect, revealing that higher energy prices had already influenced production and supply for approximately 60% of food manufacturers by March 2022, compared to only 38% of all UK businesses.

Depreciation of the sterling – Another significant factor driving policy considerations is the depreciation of the sterling against the dollar since the beginning of 2022. This depreciation has led to increased costs for importing ingredients and raw materials. A 2022 industry survey by the Food and Drink Federation highlighted that around 57% of surveyed businesses reported being significantly impacted by the weakening of the sterling.

Labour shortages – Labour shortages also emerge as a critical concern. Stakeholders unanimously express the persistence of unfilled vacancies in various roles and skill sets, spanning from high-skilled positions like engineers and R&D scientists to production operatives. The industry recognises automation as a critical solution to address labour shortages, necessitating upskilling the existing workforce. Stakeholders emphasise the need for sector-wide efforts to align the education system with industry demands to provide the necessary skills for the future.

Sustainability – Looking toward the long term, stakeholders underscore several threats to the stability and sustainability of food ingredients and inputs. These include climate change, biodiversity loss, soil and water-quality degradation, and the over-exploitation of natural capital resources. Climate change, in particular, is a significant factor in medium-to-long-term risks to domestic UK food and beverage production. Instances like the 40% drop in wheat yields in 2020 due to heavy rainfall and droughts signal potential future challenges that could compromise the resilience of the UK food system.

Sustaining innovation and growth

The UK’s food and beverage sector has made noteworthy progress in value-added, global rankings, and R&D expenditure.

However, stakeholders expressed concerns that their efforts, particularly in innovation, often go unnoticed. Industry experts emphasised that product innovation is not just a goal but a key focus for the UK food and drink sector. The latest data from Mintel (2023) unveils that in 2021 alone, over 11,600 new food and drink products were introduced, a testament to the industry’s highly competitive nature.

The very essence of the industry’s strength lies in its commitment to constant evolution. A report from the IfM (2010) underlines the industry’s push for strategic investments in R&D. This investment surge is not just a financial move; it is a deliberate strategy to fortify the sector against future challenges.

This article draws from Section 3 of the 2023 Innovation Report. Values reported are US$ unless identified otherwise to aid in international comparisons.

For data, references, and more analysis on the UK’s competitive advantage, including sectoral analysis of productivity and whether the UK is capturing value from the net zero transition, see the full 2023 Innovation Report produced by Cambridge Industrial Innovation Policy.

For further information please contact:

David Leal-Ayala

+44(0)1223 764908drl38@cam.ac.uk13th February 2026

The UK Manufacturing Dashboard: a tool for evidence-based industrial policy

News | 6th February 2026

UK Manufacturing Dashboard: latest performance and global benchmarks

3rd February 2026

The Swiss paradox: a services reputation built on an industrial and innovation powerhouse

Get in touch to find out more about working with us