Reports and articles

Moving differently: why the transport we use matters for reducing carbon emissions

Published on May 7th 2024

With the UK’s continuing traffic growth, the country increasingly relies on electric vehicles to reduce domestic transport emissions. But how can we speed up and complement these efforts?

In this guest blog, Hugh Thomas, a PhD student from the Department of Engineering, draws on his latest article, ‘Using different transport modes: An opportunity to reduce UK passenger transport emissions?’ co-authored with Dr André Cabrera Serrenho, to explore ways we can speed up our efforts to reduce emissions and make our transportation more sustainable.

Reducing emissions: changing how we travel in the UK

Transportation is currently the UK’s largest emitting sector, responsible for approximately one-third of all territorial emissions.

While technological advancements have increased the energy efficiency of new vehicles, the potential emissions savings from efficiency gains have been offset by an increase in transport activity. This increase has occurred alongside a shift in consumer preferences towards larger cars and a rise in the proportion of trips made in private cars.

Figure 1: Historical changes in modes of transport used for domestic travel. Source: Transport Statistics Great Britain: 2019 (publishing.service.gov.uk)

However, it is possible to significantly reduce emissions by changing personal travel habits and by reversing the trend of using private cars. Even without any changes to public transport capacity, vehicle availability, or population travel destinations, domestic transport emissions can be reduced by up to 31%.

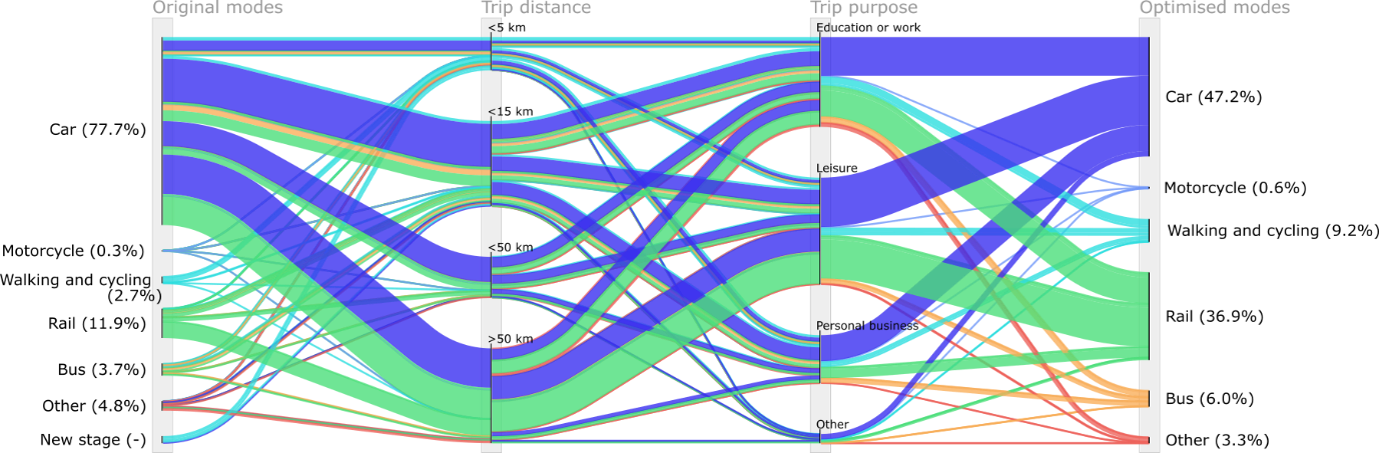

According to our recent article, an emissions optimisation model shows that this would be achieved by tripling the distance travelled by walking, cycling and rail, almost doubling the distance travelled by bus and reducing the proportion of total distance travelled by car by 30% (see figure 2).

Shifting to slower modes of transportation, such as public transport, would only increase daily travel time by an average of 5 minutes. Moreover, these shifts can happen immediately, as the decision of which transport mode to use is often only made shortly before the trip occurs. Conversely, the emissions saving from replacing fossil fuel-powered vehicles with electric alternatives is gradual, as emissions savings are only realised when vehicles are replaced, which is often well over 10 years after a new vehicle is purchased.

Figure 2: Shifts in passenger-km travelled required to reduce emissions by 31%.

Encouraging a shift towards sustainable transport modes

Despite these shifts being theoretically possible, achieving higher walking and cycling rates and greater public transport use would require a shift in people’s behaviours and preferences.

One method of stimulating these behaviour changes could be through infrastructure development and providing better quality services to increase competition with private car use. For example, 55% of respondents to the National Travel Attitudes Survey identified the provision of off-road and segregated cycle lanes as an incentive that would encourage them to cycle more. Furthermore, the main reason given by infrequent rail users for not using rail services more often was that it was easier to use a car.

Going the extra mile in emission savings

In addition to the immediate 31% transport emissions savings that can be achieved by using different transport modes, longer-term emissions savings are feasible through increasing public transport capacity on certain modes, changing vehicle availability, and increasing the time people typically spend travelling.

Increasing rail capacity is crucial to avoid overcrowding and infrastructure limitations, allowing for more passengers to take the train. Furthermore, increasing the availability of bicycles so that they are an option for every trip could increase the potential emissions reduction from 31% of domestic transport emissions to 33%, without any increases in the time spent travelling.

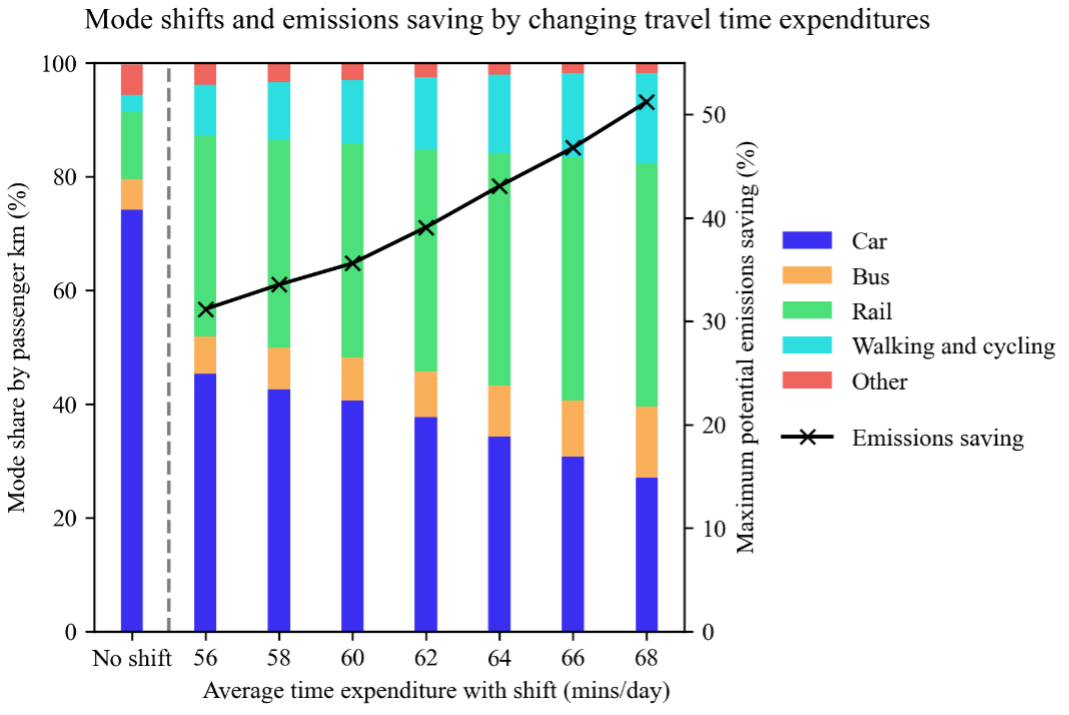

However, if people are willing to spend more time travelling, the potential emissions savings from using different transport modes are dramatically increased. If the average time spent travelling increased from 52 to 68 minutes/day then overall domestic transport emissions could be reduced by just over 50%, given that slower transport modes tend to be less emission-intensive than faster modes (see figure 3).

Figure 3: Change in possible emissions savings as the average time expenditure is changed.

Policy considerations

Whilst some actions and targets in the UK transport decarbonisation strategy explicitly address changing transport modes, such as the target for half of all journeys in towns and cities to be made by walking or cycling by 2030, there is still significant untapped potential to reduce emissions through using different types of transport.

If the UK government were to put greater emphasis on changing transport modes, several measures could be considered:

- Targets for different transport mode usage. Setting targets for increased public transport use, similar to those for walking and cycling, would allow for progress in stimulating behaviour change to be measured across the full range of transport options.

- Methods of reducing the costs of time spent travelling. The opportunity cost of travelling could be reduced by improving people’s ability to be productive on public transport, for example by improving comfort levels and increasing reliability, and by improving awareness of the benefits of using other modes of transport.

- Providing infrastructure that makes active and public transport attractive versus private car use. Reducing the barriers to active and public transport is necessary to shift public behaviours and perceptions around the options for travel. For example, converting areas to low traffic neighbourhoods can reduce traffic volumes, making streets safer for walking and cycling.

This blog is based on the article: ‘Using different transport modes: An opportunity to reduce UK passenger transport emissions?’ authored by Hugh Thomas and Dr André Cabrera Serrenho in the Department of Engineering, University of Cambridge.

Download the full article: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2023.103989

For further information please contact:

David Leal-Ayala

+44(0)1223 764908drl38@cam.ac.ukRelated resources

News | 6th February 2026

UK Manufacturing Dashboard: latest performance and global benchmarks

3rd February 2026

The Swiss paradox: a services reputation built on an industrial and innovation powerhouse

News | 21st January 2026

CIIP delivers bespoke training for delegation from the Government of Nigeria

Find out more about how our community supports governments and global organisations in industrial innovation policy