Reports and articles

Selling less and buying more: the worsening trade balance of the UK pharmaceutical industry

Published on June 22nd 2022

The UK’s global ranking in pharmaceutical trade balance has dropped from 4th to 98th over the last decade. Senior Policy Analyst Dr Liz Killen draws upon findings from the 2022 UK Innovation Report to look at the reasons why.

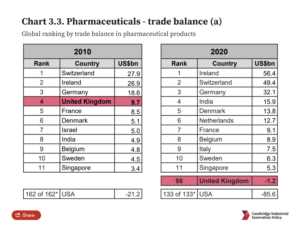

If you took a snapshot from the year 2010, you’d probably conclude that things were looking fairly good for the UK pharmaceutical industry. In 2010, the UK exported more pharmaceutical products than any other country except Germany, Switzerland, the US, and France, ranking it 5th in global pharmaceutical exports, and 4th in the overall global trade balance in pharmaceuticals.

Forward on to 2020, and the UK has plummeted to 98th on the global rankings in overall trade balance in pharmaceuticals. This represents a decline from a $9.7 billion surplus in 2010 to a $1 billion trade deficit in pharmaceuticals in 2020. The UK’s pharmaceutical exports have declined while its imports have increased. So, what has happened in the last decade to the UK’s pharmaceutical industry?

Four reasons for the reduction in trade competitiveness

For the 2022 UK Innovation Report, published annually by our team at Cambridge Industrial Innovation Policy, we consulted sectoral experts and reviewed the literature in order to understand the drivers behind these trends.

There were four key themes that arose from these discussions.

- The UK has become a less attractive destination for pharmaceutical investment compared to other nations

Increasing attractiveness of overseas nations as an investment location, as well as local factors undermining the UK’s own position, have reduced the UK’s inability to capture international manufacturing investments.The UK’s 2017 Life Sciences Industrial Strategy identified that the second wave of manufacturing investments on new plant and equipment for the manufacture of biologics and other novel medicines went largely to Ireland, Singapore, Germany and the US, which together attracted the bulk of S$125 billion investment between 2011 and 2017.In addition to market size and workforce skills, incentives offered by other countries included lower business tax rates and other financial incentives to attract research and development (R&D) investment. Experts also identified that the 2016 EU membership referendum has added uncertainty to investment decisions. - Restructuring and site closures by major multinationals impacted pharmaceutical manufacturing in the UK

This change in attractiveness for investment was reflected in the actions of some multinational corporations – company restructuring and site closures by major sector employers, for example. There was also the increased offshoring of pharmaceutical manufacturing, including a large share of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). For many multinational pharmaceutical companies, decisions on the location for significant R&D investment and expenditure are being made by overseas headquarters. - UK R&D decisions may be affected by weaknesses in the commercialisation and scale-up pipeline

Part of the trend may be the system-level effects of characteristics of individual businesses within the UK pharmaceutical industry. This includes UK companies reducing in-house R&D investment in favour of acquiring small firms, and new entrants focusing on early-stage drug discovery and non-manufacturing activities.However, for these trends to produce a disadvantage comparative to other nations, this must be accompanied by a weakness in the commercialisation and scale-up pipeline for technologies developed in the UK. This can lead to cases where breakthroughs are ‘invented here, produced elsewhere’, where technologies developed in the UK are commercialised and manufactured abroad. For example, despite the discovery of monoclonal antibodies in the UK, the UK has failed to capitalise on this by securing commercial manufacturing of these products. - Domestic policy may have had unintended impacts on the local pharmaceutical industry

Domestic UK policy can be used to support the pharmaceutical industry, but certain policy decisions may have inadvertent negative effects. For example, caps on NHS drug spending may be having an impact on the perception of the profitability of the UK’s domestic market by investors, particularly now that it has withdrawn from the EU’s single market. More generally, increased use of generics, while pushing prices downwards for consumers, most often involves driving total volumes of imports upwards. Smaller firms also identified difficulties accessing scale-up funding locally, leading to firms’ decisions to migrate.

Country-by-country analysis

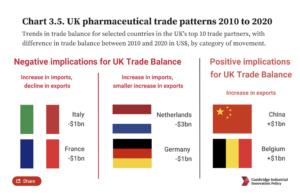

In addition to gathering expert judgements, analysing the changes in Britain’s top trade partners can provide more detail on both challenges and opportunities for the industry. For the 2022 UK Innovation Report, we looked at the changes to the UK’s top 10 trade partners, and this showed that the picture is not uniformly one of decline.

For many European countries, the picture was one of worsening trade balances over the decade. In both Italy and France, imports rose while exports fell, resulting in a net reduction of just over £1 billion in trade for each country over the decade.

For some of the UK’s top trading partners, both imports and exports grew, but the rise in imports was outstripped by the growth in exports. This was true for the Netherlands, with a 14.4% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) in imports and only a 1.5% annual growth in UK exports, to a tune of £3.2 billion lower trade balance in 2020 compared to 2010. The picture was similar, but to a lesser extent, in Germany, with 4.4% CAGR imports vs 0.9% CAGR UK exports and a £700 million difference in trade balance in 2020 compared to 2010.

The picture is not all doom and gloom however, and there have been some successes in UK pharmaceutical trade over the past decade. The UK has exported more medicinal and pharmaceutical products to China and Belgium, with a 13% CAGR between 2010 and 2020 for each country, bringing in £1 billion more in exports each in 2020 than 2010.

It is these new export markets that need to be capitalised on if the UK’s trade balance is to shift. While imports appear to have declined slowly from around 2016 through to the most recent 2021 data, pharmaceutical product exports appear to have remained relatively stable over the past few years. While the UK saw increases in gross value added (GVA) from pharmaceutical manufacturing of 18% between 2019 and 2021, likely to meet domestic pandemic demand, it is uncertain whether these will translate into increases in sales to export markets into 2022.

The importance of reversing these trends for the UK economy

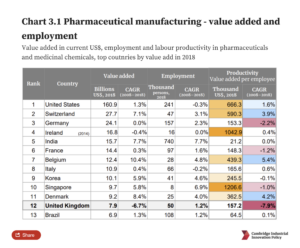

Despite recent declines in exports and productivity, the pharmaceutical industry remains a major sector of the UK economy, which contributed $7.5 billion value-added to the UK economy in 2018.

However, while the productivity (GVA per employee) of the pharmaceutical manufacturing sector is higher than average for UK sectors, it only moderate by comparison to other leading nations, and productivity declined between 2008-2018 at a rate of 7.9% per year (CAGR).

It is precisely because this high-productivity, high-value-added sector is in decline that the UK Government should take steps now to maintain the UK’s leadership in the pharmaceutical sector.

The UK possesses key capabilities and skills which can be leveraged in capturing the next wave of innovation in pharmaceuticals. There is also a strong culture of start-ups, with pharmaceuticals claiming the most university spinouts of any sector in the UK in Beauhurst’s recent analysis.

The government’s broader aim to increase UK R&D expenditure to 2.4% of gross domestic product (GDP) will only support this innovation pipeline, which could serve to anchor manufacturing and business R&D expenditure in the UK. Both the UK government and pharmaceutical industry are active in promoting this agenda, with key policies including the Life Sciences Vision in 2021 and the Medicines Manufacturing Industry Partnership of 2017.

The data reflects the larger economic forces that have buffeted the UK’s pharmaceutical industry over the past decade. But Britain retains a number of competitive advantages in this sector that, if properly cultivated, could see that trade balance improve in the coming years.

This analysis draws from Section 3 of the 2022 UK Innovation Report. Values reported are US$ unless identified otherwise, to aid in international comparisons.

For data, references, and more analysis on the UK’s competitive advantage, including sectoral analysis of productivity, and whether the UK is capturing value from the net zero transition, see the full 2022 UK Innovation Report, produced by the Policy Links team at Cambridge Industrial Innovation Policy.

For further information please contact:

Ella Whellams

+44 (0) 1223 748262erd30@cam.ac.ukDr Liz Killen is a Senior Policy Analyst within the Policy Links team of IfM Engage. This blog was informed by work conducted by Dr David Leal-Ayala, Dr Carlos Lopez-Gomez, Dr Jennifer Castenada-Navarrete, and Dr Michele Palladino.

You can contact Liz and the Policy Links team at Cambridge Industrial Innovation Policy at ifm-policy-links@eng.cam.ac.uk

Related resources

News | 6th February 2026

UK Manufacturing Dashboard: latest performance and global benchmarks

3rd February 2026

The Swiss paradox: a services reputation built on an industrial and innovation powerhouse

News | 21st January 2026

CIIP delivers bespoke training for delegation from the Government of Nigeria

Read more about some of our recent projects